History is usually told from the perspective of whoever wrote it. Colonial rule, for example. What was, in reality, political and economic exploitation of subjugated nations, is now said to have been imperative for the spread of civilization. Arguably, this is true. Colonization did result in the rapid growth of industries and economies through the 19th and 20th centuries. In Europe. Within the colonies however, poverty and disease were rampant during this period. In British colonies, while roads and railways were constructed to open up regions for farming and mining, local communities were pushed out of their lands and stripped of their livelihoods. They were then put to work for very low wages and taxed heavily.

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, the British Empire comprised of thirteen colonies across the world. Each of these colonies was majorly targeted as a source for raw materials. Countries like those in the Carribean and East Africa had vast arable land for farming while those in West and South Africa were rich in minerals. The labour required for these enterprises, especially in farming, was immense and for a great period of time was provided by African slaves. However, with the abolition of slavery by the British government in 1833 a sustainable replacement was needed. The labour was soon to be found in the form of Indian indentured servants.

At the time of abolition, the British had stratified Indian society by class, religion and skin colour. The decision was based off of the caste system found in ancient Hindu texts (Manusmriti). Governance over the country was then implemented through this system. This was despite the lack of evidence that it was already a part of Indian society prior to British arrival.

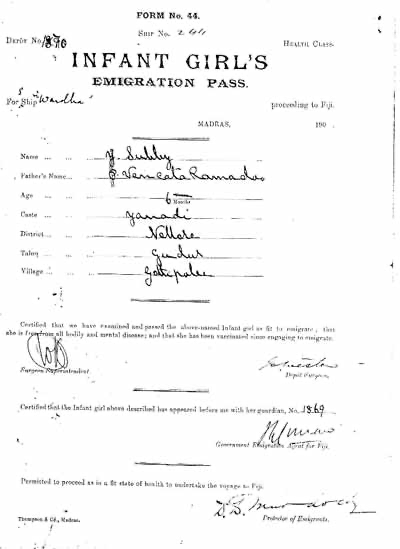

Between 1838 and the 1920s, over one and a half million Indians would be shipped to various British colonies for indentured servitude. Recruitment was done locally with the targeted being the impoverished. Many of these lived up in the mountains and had little to no knowledge of the outside world. During the recruitment process, they would meet with an agent who would give them incorrect or misleading information. Some were told that they were going to work in a neighboring town only to later be informed that they would infact be shipped out of the country. A contract would then be signed (a fingerprint being used instead of a written signature) whereby the individuals agreed to work for a specific period of time, usually five to ten years, for compensation. Hundreds of men, women and children were then packed into a single ship for months on end to the Americas and Africa. A majority of these laborers belonged to the lower castes. At the end of their journeys they would alight on foreign land and find, despite the promises made by their agents, low to no salaries, disease, and oppression. Many of those shipped across the world would never see their homes again.

Jeevanjee and the Railway

A.M. Jeevanjee was an Indian merchant and entrepreneur. His arrival (among many others) signaled what could be regarded as the second group of Indian immigrants into East Africa (The first being the coastal port traders from the late 15th century). These immigrants were known as “free immigrants”. They came as traders and skilled labourers looking for new opportunities. This was as a result of enticement by the British, who regarded Kenya as the “America for the Hindu”. The dystopian promise was so great that by 1924 a great number of Indians had settled into the new colony. They opened up shops (dukawallahs) and service based businesses in the towns that had began developing across the colony. These towns were growing as a consequene of the construction of the Uganda Railway.

The railway was a successor of the Mackinnon-Sclater Road -that linked Mombasa to Uganda via Busia- in the transportation of goods. It was meant to open up land for agriculture by European settlers, with even a proposition being made to the Zionist Organization for occupation in Kenya by Jews (the proposition was denied, however).

Jeevanjee built his wealth by being contracted as an agent by the colonial government to supply labor for the project. Between the years 1895 and 1902, Jeevanjee shipped 31,983 indentured servants to East Africa from India. Out of these, almost 2500 died from dilapidating conditions. Of those who remained, two thirds left once construction was over, unlike their counterparts in other countries.

“Many […] tried to escape the harsh conditions but were recaptured and imprisoned.” – Striking Women.

Life After The Railway

The railway was completed in 1901. Towns, like Nairobi that had sprouted alongside it flourished with the businesses being introduced, mainly by Indian immigrants. It was from this that the town’s economic backbone was built. The other two groups occupying Nairobi were young Africans who constituted the work force and the Europeans who ran government (as well as controlling the country’s agricultural sector).

Segregation was also widely implemented in Nairobi at this time. This was especially clear in government planning for housing. Europeans occupied the lush green areas of the town where the colonial government provided ample roads and plumbing. Adjacent suburbs were reserved for the Indian community with whatever was left being given to the Africans working in Nairobi. Although sometimes this would not be enough resulting in Africans being evicted from their homes for development of Indian and European neighborhoods – such as what happened in Pangani. However, these living situations were not always clear cut. Less wealthy Indians lived alongside Africans within the town and in the Indian bazaar.

The bazaar would soon be bought by A.M. Jeevanjee (who at this point had become one of the wealthiest men in the colony) in 1901. Lower class Indians would trade and live in the bazaar as well as provide boarding for Africans. Despite being riddled by disease and poor sanitation due to a lack of provision of proper plumbing by the colonial government, the market grew to become a center of trade in Nairobi.

The stratification of social classes within the Indian community in Nairobi at the time would suggest that not all the immigrants achieved much of the same levels of opportunities that the new colony offered. Many of those who came as free immigrants, such as the businessman Kassam Kanji Rahim Varsi, came with the assistance of their communities like the Ismaili Community of the Aga Khan, as well as from family and friends. This assistance allowed them work, apprenticeship and sometimes even capital to grow their own businesses in the colony. While those who came as railway workers and stayed after construction was over, continued working for the railway company. They might or might not have accumulated enough to start their own businesses as well.

It would be false to assume that all those who came as free immigrants had assistance or the same access to opportunities, and that all those who remained as railway workers did not succeed. From the three groups of Indian immigrants into East Africa, different individuals could have created their wealth in a variety of ways. However, it is safe to say that a good number of the railway workers who stayed in the country might not have found the same level of success as their counterparts who came as free immigrants or as traders on the Mombasa port in precolonial Kenya. Also, taking into account that these railway workers came from the lower classes in India, it could be assumed that they constituted the lower classes in Kenya as well -since the caste sytem was prevalent in the Indian communities in East Africa during the colonial era.

All these assumptions are built on the lack of conversation around the actual human beings who laid the railway on the ground. Instead, the focus has been on the metal snake itself, on the British politicians who conceptualised the idea and the engineers who are revered for this “noble project”. But the railway was not noble at all. It was a tool, like many others, for British colonisation. While the people who suffered for this malignant cause remain unnamed and faceless in a distorted history book.

Very informative and interesting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you enjoyed the read:)

LikeLike